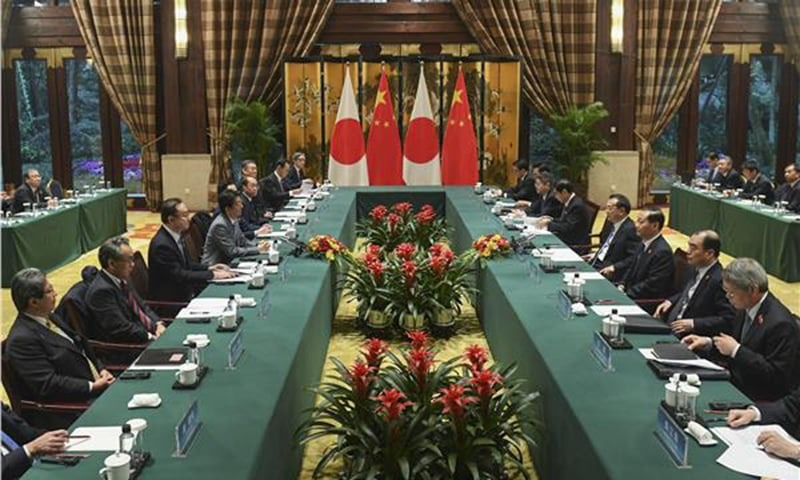

China hosted the leaders of squabbling neighbours South Korea and Japan for their first official meeting in over a year on Tuesday, flexing its diplomatic muscle with America’s two key Asian allies and seeking unity on how to deal with a belligerent North Korea.

The gathering in the southwestern city of Chengdu was held with the clock ticking on a threatened “Christmas gift” from North Korean leader Kim Jong Un that could reignite global tensions over its nuclear programme.

Kim has promised the unidentified “gift” — which analysts and American officials believe could be a provocative missile test — if the US does not make concessions in their nuclear talks by the end of the year.

The gathering also featured the first bilateral meeting between South Korea’s Moon Jae-in and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 15 months.

Ties between the two have hit rock bottom lately over trade issues and other disputes related to decades of bitter wrangling over Japan’s 1910-1945 occupation of the Korean peninsula.

The United States has urged the pair to bury the hatchet — worried their poor relations were complicating diplomacy in Asia — although it has held off on direct mediation.

China is appearing to fill that void with the Chengdu event.

“As the region’s major power, China hopes to show its diplomatic presence to the world by bringing the Japanese and South Korean leaders to the same table,” Haruko Satoh, professor and expert on Chinese politics at Osaka University, said.

Before leaving for China, Abe told reporters that links with Seoul remained “severe”.

But Abe and Moon were photographed smiling and shaking hands, and made positive overtures at the start of their bilateral meeting.

The relationship between Japan and both Koreas is overshadowed by the 35 years of brutal colonisation by the Japanese — including the use of sex slaves and forced labour — that is still bitterly resented today.

Ties began a downward spiral in recent months after a series of South Korean court rulings ordering Japanese firms to compensate wartime forced labour victims.

These infuriated Tokyo, who insisted the matter had been settled by a 1965 treaty between the two countries.

Seoul then threatened to withdraw from a key military intelligence-sharing pact, although it reversed course in November and agreed to extend it “conditionally”.

Abe said he hoped “to improve the important Japan-South Korea relations and to exchange candid opinions”, according to Japanese public broadcaster NHK.