Fifty years after a mighty Saturn V rocket set off from Florida carrying the first humans to the Moon, a veteran of the Apollo 11 crew returned to the fabled launch pad on Tuesday to commemorate the event that defined an era.

“We crew felt the weight of the world on our shoulders, we knew that everyone would be looking at us, friend or foe,” command module pilot Michael Collins said from the Kennedy Space Centre.

He and Buzz Aldrin, who piloted the lunar module that detached from the spacecraft and landed on the Moon’s surface, are the two surviving members from the mission that would change the way humanity saw its place in the universe.

Their commander Neil Armstrong, the first man on the Moon, passed away in 2012 aged 82.

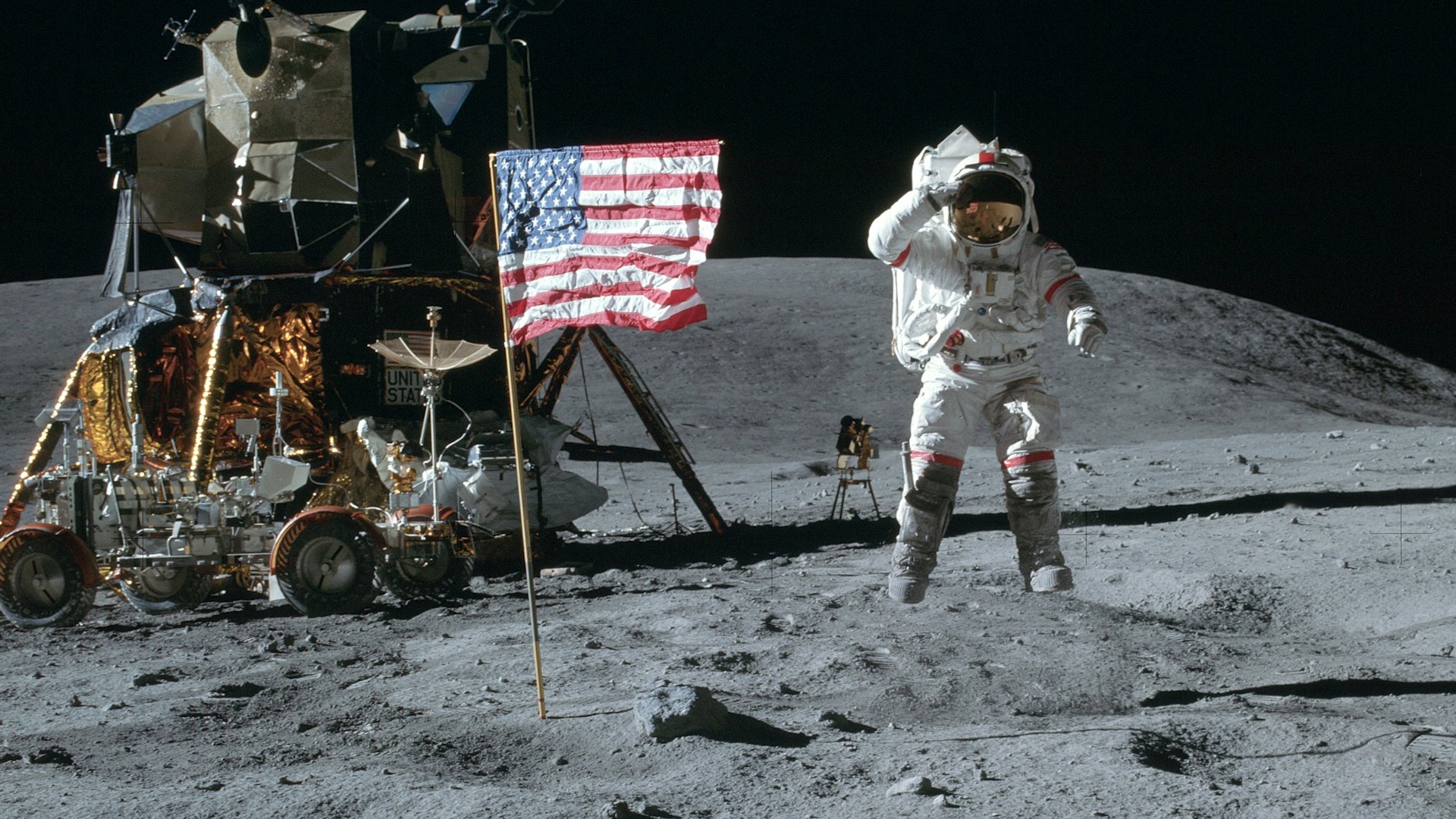

Their spacecraft took four days to reach the Moon, before the module known as “Eagle” touched the lunar surface on July 20, 1969. Armstrong emerged a few hours later.

Collins remained in lunar orbit in the command module Columbia, their only means of returning back to Earth.

“I always think of a flight to the moon as being a long and fragile daisy chain of events,” the 88-year-old said at the first of several events planned across the week to mark the anniversary.

Collins described how the mission was broken into discrete goals such as going faster than the Earth’s escape velocity — the speed needed to break free of the planet’s gravitational pull — or slowing down for lunar orbit.

“The flight was a question of being under tension worrying about what’s coming next. What do I have to do now to keep this daisy chain intact?” Aldrin has remained relatively more elusive and did not participate at Tuesday’s launchpad event.

Aging but active on Twitter, and always seen in stars-and-stripes socks, the 89-year-old has faced health scares and family feuds, culminating in a court case over finances, which was settled in March.

He is the second man to have stepped foot on the Moon. Only four of the 12 men who have done so remain alive.

Collins, however has been fielding questions for half a century about whether he felt lonely or left out.

“I was always asked wasn’t I the loneliest person in the whole lonely history of the whole lonely solar system when I was by myself in that lonely orbit?” he said. “And the answer was ‘No, I felt fine!’” “I was very happy to be where I was and to see this complicated mission unfold.

“I would enjoy a perfectly enjoyable hot coffee, I had music if I wanted to. Good old Command Module Columbia had every facility that I needed, and it was plenty big and I really enjoyed my time by myself instead of being terribly lonely.” Collins added he was offered the chance to be commander of Apollo 17, but turned it down because he did not want to spend another three years living on the road away from his wife and young children.

Despite the festivities, neither the United States nor any other country has managed to return a human to the Moon since 1972, the year of the final Apollo mission.

President George H.W. Bush promised to do so in 1989, as did his son president George W. Bush in 2004, while pledging to also march forward to Mars.

But they both ran up against a Congress that wasn’t inclined to fund the adventures, and the tide of public opinion had also turned since president John F. Kennedy roused the nation to action in the 1960s.

For his part, President Donald Trump relaunched the race to re-conquer the Moon and Mars after taking office in 2017. But the immediate effect has been to create turbulence within the space agency.

Last week, Nasa administrator Jim Bridenstine fired the head of the human space exploration directorate Bill Gerstenmaier, likely over disagreements over the 2024 ultimatum set by Trump to return an American to the Moon.

Five years appears unlikely given that neither the rocket, capsule or lander are yet ready or even finalised.

“We don’t have a lot of time to waste, if we’re going to have new leadership, it needs to happen now,” Bridenstine told CSPAN last week.